I’ve been working as a test consultant for a year at my current client and I constantly wonder what problem next I can help fixing.

The IT department has grown immensely since last year. Not just in numbers, but in maturity as well. I’m very proud of how much progression these guys have made.

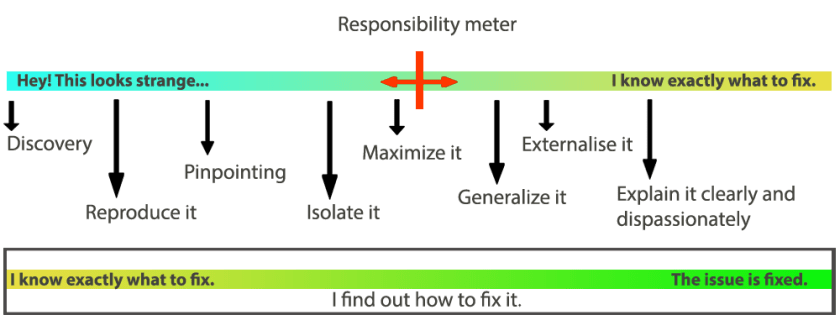

Yet, the laws of consulting state that there always is a problem and that it is quite certain to be a people problem. And so we identified our current number one problem to be: “Still many people don’t know what to expect of us, testers, or don’t know what we actually do.”

We’ve had managers asking us to do gatekeeping, exhaustive testing,… Programmers asking us to test systems that don’t have an interface, do implementation level testing,…

We decided to create some kind of manifesto. A clear set of rules and statements that best describe our core business. This is what came of it: This is a first version and hasn’t been put up yet, but we feel we’re getting close.

This is a first version and hasn’t been put up yet, but we feel we’re getting close.

The testers felt the need to create a concise, to-the-point document which we’d print in large and raise on our wall as a flag. They want to be understood and grow from having to hear “just test this” to “I need information about feature X regarding Y and Z”.

I, as a consultant, wanted to unite testers, programmers, analysts and managers under a common understanding of what testers do, don’t do and can’t do.

Knowing that my days at the client are numbered, I want to leave behind tools for the testers to fight their own battles, when the time comes.

I have seen us become a team that supports the IT department in diverse and effective ways. Yet recently, powers that wish to fit us back into a process box have been at play as well. I’d hate to see the team become reduced to a checkbox on a definition of done again.